Dargh and Janagast: A Retrospective

Dargh and Janagast, two Gathrani experiments in nation building

In short, they failed. How and why is a matter of debate. I shall try to untangle this brief foray into the creation of satellite states.

Hindsight is the great revealer. With years, decades, and centuries between present and past, mistakes and follies become much easier to discern. What seems, at the time, a brilliant enterprise might be revealed as doomed from the beginning in the passage of time.

Steeloak was Gathran’s biggest folly.

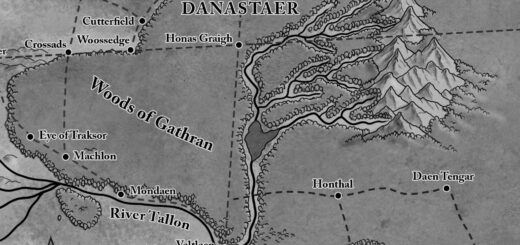

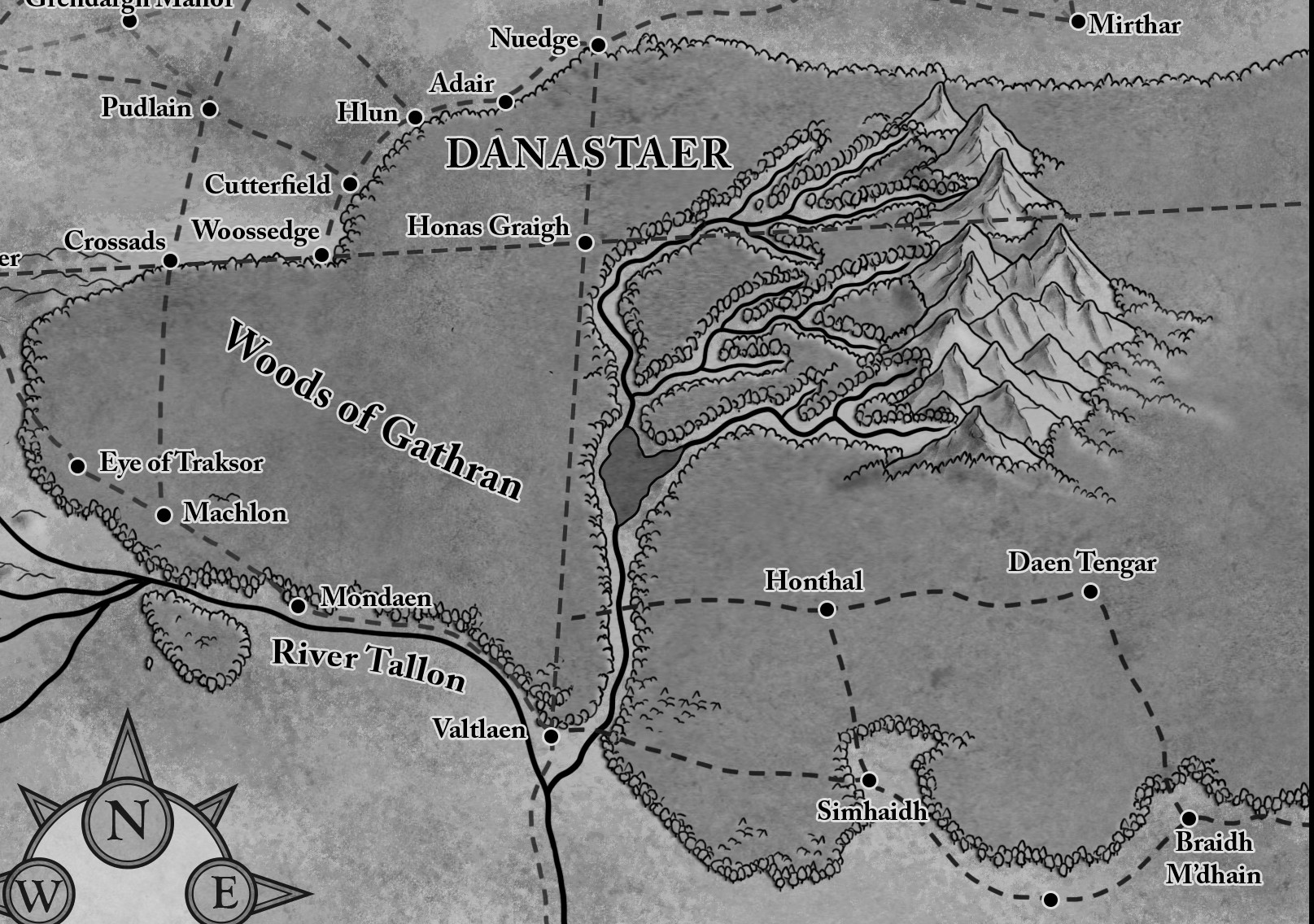

The area we now know as Gathran Forest is only a fraction of what Gathran was in the beginning. At one point in the distant past, Gathran’s steeloaks grew in the Kumeen foothills several hundred miles to the west. The Shadowpeaks were dotted with rogue steeloaks here and there, and the Flannardh was that wood’s northern boundary. Eastward, the forest petered out somewhere around the abandoned village of Little Creek, and south, the majesty of the steeloak reached almost as far as modern Ma’tallon.

From what we can tell, steeloak was a sunargh creation, one of the few lucky accidents amidst a slew of experiments gone horribly wrong. How this variant of the common oak tree came into existence lies far beyond recorded history, and the few sunarghs still alive can’t remember either. As such, this scholar believes the accident had as much to do with the immutable will of the First Ones, those progenitors of the sunargh race, and the Maid of Mischief, Cingrib herself, having a bit of fun.

The gods aren’t necessarily capricious. They prefer to observe, granting their priesthood certain boons, but rarely interfering directly. The sole exception to this rule is the Fox goddess. But what might have been a bit of fun turned into something worse. Or rather, it spread into something worse. And though we’ve showered vagabonds and homeless with gifts, begging for the goddess to reveal what truly happened, all we ever got in return was howling laughter, and a rather firm “Fuck off.” (I can’t express how much I laughed at this one. ~O)

In the end all that remained was guesswork. Steeloaks only grow within the borders described above, beyond that line, every sapling, every seed dies. This can mean one of two things: the trees were only ever intended to grow in this area, or the gods themselves prevented the trees from spreading even further. I’m inclined to think the latter is true, as no amount of testing could distinguish soil samples from either side of this invisible demarcation line. We couldn’t determine any magical influence either, but the gods are beholden to their own rules. There has never been a recorded detection of divine interference, even when a clergymember was involved, so it was concluded that a) it must have been the gods stopping the further spread of steeloak, and b) the spread that did occur must have been a mishap.

Steeloaks are symbiotic, the seedlings or saplings latch onto already growing trees and then, in a matter of weeks, completely subvert the entire plant. (Technically that’s not symbiosis. ~J) (Pretty sure the author knew that, but is there a better term? ~T) A jokester friend of mine once said, “Steeloaks are the red socks in a pile of white laundry: wash them together and everything turns rather reddish. (Oooh, I like that! ~T) (Me too. ~J) Only these socks turn everything they touch into socks as well.” It’s a hostile takeover, literally. And whatever the original intention, I’m fairly certain it did not involve turning swathes of wooded land into swathes of nigh-indestructible trees.

The Gathrani homeland lay at the foot of the sole mountain poking up from a canopy of steeloaks, after the sunarghs were defeated. There they survived rather than thrived, every bit of arable land was farmed, and the surviving cave-dwellings speak of harsh living conditions. How the Gathrani discovered the way to cut down the steeloaks that surrounded them is something no outsider has ever managed to unearth. Spies were ruthlessly slaughtered throughout Gathrani reign in the woods that bear their name.

What, pray tell, does this have to do with the histories of Dargh and Janagast, one may ask? The answer is quite simple: with their insatiable demand for steeloak, and due to their subsequent negligence at replanting new trees, the elves of Gathran denuded the vast swathes of woodland until the great steeloaks simply lost their foothold. (They also forgot to replant new trees. Thus denying the ability for steeloaks to repopulate the area. ~H) (It must be remarked that, should a steeloak sapling be “released” near another tree within the ancient boundaries, this tree would be subsumed and become a new steeloak. Sadly, or maybe fortunately, this regrowth only works when there is a growth of steeloaks nearby or someone has gone through the procedure of taking a sapling to that tree. This in turn will result in the spread of more steeloaks in the area surrounding this new tree. ~L) (Provided the tree wasn’t solitary, of course. ~O) (It must also be noted that certain types of trees seem to have developed a resistance to being subsumed by steeloak “infestation.” ~W) (Or maybe some magical experiment resulted in that immunity? ~G)

Steeloaks never reconquered the deforested areas, and even though other trees grew, much of the freed area now served as farmland – a welcome side-effect to the wanton destruction of the woodlands. As more and more arable land became available, Honas Graigh’s population multiplied. The North-South Road was built, waystations provided travelers with much needed supplies, and things barely changed until the Contraction, and the arrival of humans. (There are some people who surmise that the gods’ interference went even further . . . that after the initial onslaught of steeloaks, the gods, more specifically Chanlhaian, saw to it that growth even within the “infected” region could not spread any further. This is one of a few explanations, or attempted explanations, as to why we now find steeloaks growing next to birch and oak and fir within the Woods of Gathran. ~F)

At that time, around the year 500 K.C., Gathran, the Empire, had ceased to exist, and every realm in Taogh scrambled to adapt to this sudden influx of strangers. Gathran, now little more than the forested area surrounding Honas Graigh, had been the first nation to stop enslaving the newcomers. But they didn’t truly know what to do with them either. (Go figure. ~D) Traditions die hard, and even though the humans were neither slaves nor prisoners, they did not fit into the former empire’s social systems. The world was changing – too quickly for some of the old families. Some enterprising Houses, the biggest landowners north of Gathran, decided upon something rather unique: They gave the land to the humans, under the condition that they worked the land and provided a percentage of their harvests to their elven benefactors.

So it happened that the Houses of Dargh and Janaith and Gasteen leased their property to human tenants. Dargh, by far the biggest of the three, controlled the lands west of the North-South Road, while Janaith and Gasteen controlled the lands to the east. Over time, wealthy humans eked out their own little realms within these House-controlled areas; baronies were formed, which then became hereditary titles and grants, still under the Houses’ nominal rule but with more rights and duties.

Barons and baronesses were responsible for providing the required quotas, which led to complications in the lands of Houses Janaith and Gasteen. Their human nobles proved to be too greedy, cheating or attempting to betray their landlords. The response was to be expected, or at least any elf familiar with Gathrani politics knew what was bound to follow. Houses Gasteen and Janaith petitioned the Council of Mages which promptly dispatched a Leghan. The barons and their retainers were quickly executed, and both Houses consolidated their interests and laid out a plan as to how their lands were to be ruled. Where before an unspecified number of lordlings abused the system, the two Houses now chose to combine their holdings into the country called Janagast. The monarch of Janagast, – a lofty title for someone who was, essentially, a puppet controlled by Houses Gasteen and Janaith – controlled the various manorial enterprises, which in turn controlled the farms.

House Dargh’s approach was a little more involved. Their leadership screening process involved – among other things – several Lawspeakers and Upholders who verified the candidates were truthful. Though their territory was comparable in size to Janagast, they made the manorial units smaller, at least initially. Consolidation happened all the same, but initially the Houses Duasonh and Grendargh were but two of a number of freshly installed overseers to control the region’s productivity.

Over the centuries the nobles of Janagast and Dargh raided amongst themselves, something their elven patrons encouraged. This was not so much as a means to expansion, but rather, as a form of entertainment for the violence-prone elves. (As shortsightedness goes, this was the epitome. ~L) (Agreed, and the author does address the issue in the following paragraphs. ~T) (I should have refrained from commenting until I had finished reading. ~L) (How very shortsighted of you. ~T)

Humans, as it turns out, are equally as unpredictable as elves, and eventually the raids turned into something more. (Told you. ~T) House Duasonh was the first to expand its influence. Initially, said House’s sphere of influence was limited to Lower Cherkont, which comprised the lands around the River Dunth west of and including Dunthiochagh and some mining operations in the Shadowpeaks north of that city. This was before the Phoenix Wizards began building their Citadel in the mountains, and only after a treaty with both Houses, Dargh and Duasonh. Eventually, House Duasonh expanded to Higher Cherkont, which comprised the northern parts of the Shadowpeaks up to the River Flannardh initially controlled by Camlanh [now little more than a mining village] and the region of Boughaighr, which is the region east along the Dunth up to the North-South Road, including the fortresses along the Harail-Dunthiochagh route. (This expansion is particularly fascinating due to the fact that this included Dragoncrest, at least nominally, as it, at the time, still was controlled by the Guard. ~F) (Guard? Right, a more or less ceremonial assignment rewarded to a particularly dedicated Leghary. ~S) (Little did they know they were truly guarding an imprisoned god.) (How ominous. ~S) (The legends aren’t just Smoky Letters. The plinth truly is Dragh’s prison.) (Who wrote this? No initial, and the script seems somewhat stilted. And what are Smoky Letters? ~F) (They’re not wrong, though. ~D) (Smoky Letters? I think I read the expression before. ~H) (I believe you call it Fiery Tales. ~Gh) (You? And what is with the Gh? ~F) (Hoaghan, Guest to the Library. I thought it easier to identify myself as a guest this way. Besides, there are only so many letters in the alphabet, there are only so many initials one can use. ~Gh) (True but it messes with the entire mystery of who wrote what and when. All following generations riddle who wrote what and when, which is why we don’t include dates either. ~O) (Gh might have come from the lands beyond the Veil of Fire. ~K)

Dragoncrest remained under elven control until the Wizard War, despite being under nominal control of the Barons Duasonh. While a Baron Duasonh factually rules over Lower and Higher Cherkont and Boughaighr, they are usually announced as Baron of Higher Cherkont and Boughaighr with his initial sphere of influence being omitted. Whether that’s efficiency or laziness is anyone’s guess. House Dargh allowed the expansion, as House Duasonh had been well-loved by all its freeborn and villeins, and expanded that benevolence to their new aquisitions.

A note on social classes within humanity:

Noble, freeborn, villein. While slavery is virtually non-existent south of the River Flannardh – courtesy of elven influence – humans there have adopted a system that seems prevalent in Chanastardh. Villeins are property, children of villeins are property. How does one become villein? Aside from being born one, imprisonment and insurmountable debts may result in becoming a villein. (That’s a lot of repetition of the term. ~J) (Which term? ~R) (Very funny! ~J)

This penalty depends on the prisoner or debtor, as far as I can tell. Captured enemies are either ransomed or put to work. If it’s the latter, a number of years without an escape attempt or mutiny would result in the prisoner becoming a villein, they may build a house on their lord’s land and get to farm a field or douffield to feed themselves and their eventual family. They, in turn, were required to spend time working their lord’s fields as well. If satisfied with their work, a lord can set a villein free. Their children, then, will be freeborn.]

(That’s a lot of information that should be in a dedicated scroll. ~U) (We have a volunteer! ~P) (Shit! ~U) (You think it, you bring it. ~T) (Fine! ~U)

Dargh and Janagast were abandoned when the Gathrani left the world without a trace, and Chanastardh swooped in to conquer the lands, meeting with little to no resistance. The Chanastardhian High General Halmond decided to secede almost immediately, naming the new country Danastaer, an homage to his friend and mentor, one Danachamain. It must be said that Dargh retained much of its autonomy in this new nation, as it was obvious they had things well in hand even during the Heir War.

If you enjoy my content, why not buy me a coffee? Click here shoot me a few bucks.