Magic in War

Battlemagic is a wholly different animal. (See previous discussion of Practical Applications of Magic). Where a city relies on utilitarian mages, a Leghan of Gathran relies on the Obhanh.

Why pick the Gathrani Leghans as my first example? The same reason you don’t pick a pony to explain race horses. In Gathran’s Leghans of old, the Obhanh was both a ranking officer in a Canthan, and the one person who turned a band of soldiers carrying wooden arms and armor into a juggernaut of destruction. For those unfamiliar with the term, a Canthan is the smallest tactical unit in a Leghan. The average Canthan counts eighty soldiers and is led from the front by a Canthaneanh. His second in command is the Obhanh. As far as we know — the records are rather slim on this, and the Gathrani never revealed their secrets – an Obhanh is not a fully trained mage. They’re more like the countless utilitarian mages employing themselves to citizens.

However, an Obhanh is much better trained than their civilian counterparts. As mentioned earlier, the weaponry and shield of the Leghary, the Gathrani soldier, as well as their armor, are made of wood. Not just any wood, but steeloak. Battlefield analysis after the Eastern Empires defeat at the hands of Gathran a few hundred years ago showed that their arrows did not come with a metal tip. Witness reports from survivors describe waves of arrows fired into the air, only to turn into tree trunks which then came crashing down on our infantry. After they had smashed our feet into the ground, it looked as if they vanished. In fact they merely reverted to their original shape and size.

The mere thought of such a canopy of trunks slamming down on a charging enemy is worrisome enough, but when one thinks of the uses Gathran has found for other parts of their wooden armory, one understands why they managed to subdue and conquer an entire continent with relative ease. We can count ourselves lucky the gods thought it good fun to have Gathran’s nobles breed with mages to become a new noble class, thus turning everyone against the emperor and each other.

Suffice it to say, if Gathran had remained as it was before the creation of Mage Houses, Comhara would have fallen to the Leghans as well.

Defense Against Magic in War

The arms and armor race is never over. One develops a weapon to penetrate armor, forcing the opponent to respond by designing better armor or shield. And while Gathran had stopped our quest to return the former provinces into the fold of the Eastern Empire, thus reuniting much of old Gathran with our shining beacon of civilization, our keenest minds have been working on means to counter such forces the next time around. Considering there are spies everywhere, and after conferring with the Imperial Court, I’ve been permitted to write about these latest developments.

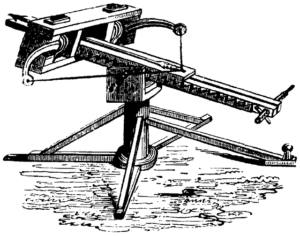

Because of their knowledge of steeloak molding, our artillery pieces do not have the range of Gathrani carphaens. Eventually wood or sinew breaks under the strain, so mages and engineers had to come up with other, similarly effective methods of raining death and destruction on an enemy.

They adapted the idea of the far eastern firepot, a container holding a mixture of elements that, upon contact with air, ignites. Water cannot quench these flames, and even steeloak will eventually burn. The pots are fired by lower tension carphaens onto advancing infantry. Why lower tension? The answer is simple: too much pressure on the container and it bursts before it leaves the catapult. (We lost a number of engineers, alchemists, and mages this way. ~K)

The missiles’ low velocity means the enemy can avoid it by merely stepping aside. The problem for them is that the liquid inside splashes in all directions, igniting whatever it touches. Also – and this is where the mages come in: the mechanism pulling back the string remembers being cranked back. Minor mages, similar in some ways to Gathrani Obhanhs, are attached to a battery of carphaens, all lined up together and firing at the same moment. It doesn’t matter if you dodge one missile, there’s two to one side and three to the other side of the one you just evaded. Preliminary reports from the eastern front against the Ithari nation of Blýthan say this weapon is very effective.

I’m also fairly certain the Blýthanean engineers and mages and alchemists are already working on something to counter our concoction. That’s war, that’s progress, you develop bow and arrow, and they develop shields. It’s the same litany played over and over throughout history.

Mages on the battlefield, especially with engines of war are very effective. Gathran relied on her Obhanhs, we of the Eastern Empire rely on our engineers and mages, the gods only know what the people of Gengharaidh, for example, use magic for on the battlefield.

Humans learned limited uses for magic, but they developed some methods of their own, basically reaching the same conclusion as we, only millennia later. Pebbles remember being boulders. Sand remembers being stone. Wind remembers being icy – part of a blizzard, perhaps, or that it brushed one of the active volcanoes in the Veil of Fire. Their methods are crude as they lack the time it takes to study boulders turning into pebbles turning into sand, so they extrapolate, alter time-honored formulae, creating new spells. These spells, however, require a lot of testing and refining, and the casters must truly trust magic, something very few ever achieve.

Bloodmagic in War

If a human mage destroys something, or forces something to remain standing despite its obvious destruction, they rely on Bloodmagic, creating Fact out of all the Potential trapped in an item, be it a wall or a house about to be destroyed.

Bloodmagic is so different from Potential that it’s hard to understand, harder to explain, impossibly easy to use, and equally dangerous to the mage.

Imagine . . . anything. Want a head ripped from the neck? Blood can do it, or rather the Potential in one’s blood can. You see, most mages don’t care to explore how this kind of magic works. The First Ones and their scions, the sunargh, knew what it takes to turn Potential into Fact. We only use the term Bloodmagic because it sounds more menacing than Fact Magic – a rather tame label for something so violent. It’s akin to saying forceful questioning instead of torture. Nowadays, only the most inquisitive of mages, those who dig into magic’s past, are willing and able to discern the truth. To turn Potential into Fact requires the sacrifice of Potential. Without the Lady Ice birthing the Lord of Sun and War, whose mere existence in turn diminished his mother, flooding the world in magic-rich water, which in turn allowed for life to exist, there’s always a cost when changing Potential to Fact.

As such, the only limit to a Bloodmage’s spellwork is their imagination and the Potential of the blood sacrificed. The first generation of sunargh was only two steps removed from the divine, their parents being one step away from the gods. A drop of First One’s blood literally could move mountains, or enspell a gorge never to permit water. Their descendants weren’t much weaker. One drop – poke a needle into your finger and draw a drop of blood. If the needle goes in too deep, it might be more, too shallow a puncture, and there’d be no blood at all. It takes a different kind of practice and discipline to master such. And while the First Ones had eons to develop this use of magic, their descendants were not as patient.

Imagine a child, impatient, needing a toy now. Would the child wait for the parent to explain how to get the toy safely? Not if it has the means to get it now, damn the cost. Soon the scions of the First Ones began to use their relatives’ blood instead of their own.

Bloodmagic, as I’ve mentioned, is only limited by the blood itself. It does not have to be one’s own blood – your neighbor’s suffices. I’m certain you can imagine that things got out of hand rather quickly. The sunarghs built magnificent cities, not on the backs of slaves but with the blood of their enemies, for they had decided not to poach their own. Petty rivalries spun out of control, one pride raided another, taking as many captives as they could. Retaliatory raids were the consequence, and the city states of the sunargh diminished each other even as they grew more and more magnificent.

One does not need to study the growth of trees, or how a boulder becomes a pebble, or how a volcano boils the air. All it takes is the will, and blood. The more Potential in the blood, the better the result, and the less blood used. You can probably imagine where this is headed. The most Potential is in the blood of the young because their future lies ahead of them. When the gods seeded the world with us elves, we became their new commodity, and source for blood. Old sources talk of breeding farms, where the sunargh forced males and females to mate, the women carrying the children to term only to have the babes ripped away from them upon birth. To the sunargh it was better than to raid an already diminishing foe. Not that any of the city states were better off.

There are no limits as to what Bloodmagic can do, short of challenging the gods themselves. Meld two bodies into one? I’ve seen the notes on this. I’ve already mentioned moving mountains. A twisted mind could, hypothetically, merge all kinds of beasts, bear, mountain lion, wolf, eagle, into one abomination of a creature. Even add human or elf into the mix.

Would such a being want to live, provided it was self-aware? Would you? The gods may view our plight with amusement, but they’re never cruel. We are the monsters. They give us the rules, promise our souls an existence as chamber pots in the afterlife if we deviate from them, but how many actually take these rules to heart? How many selfish, greedy people are among the elves? How many among the humans? One would think that the threat of having the souls of the worthy shit into you is deterrent enough.

Are we any better than the sunargh? The butchers kept elves as slaves, bred us like livestock, bled us dry to feed their spells, used our skins for parchment. The irony isn’t lost on me, either, as I write my thoughts on this scroll of parchment. Did the sunargh care about our feelings? Do we care about the cow or bull being slaughtered and skinned for food and writing material? Most probably never will; some will argue the cow isn’t sentient, thus not worth of any consideration. Did the sunargh view us as not worth of consideration? How would we, or humans, react if someone said “Cows have feelings”? Would it change our lives or would we laugh at the speaker?

To a sunargh, we might as well be cattle. And if we look at how many elves across the hemisphere have segregated themselves from humanity because they don’t want anything to do with the primitives, maybe the cow is sentient? Maybe the gods already decided to give cows or horses intelligence, just for their amusement? Who knows?

Courtesy of the Lightbringer reminding the elves of Taogh how they were treated by the sunargh, a repetition of the past could be avoided, but we were on our way to be as vile to them as the slave-masters were to us.

Bloodmagic is only a symptom, a very brutal and frightening symptom, but still. The First Ones had mastered it, without resorting to butchering each other.

We kill each other in arenas or on battlefields. Are we any better?

If you enjoy my content, why not buy me a coffee? Click here shoot me a few bucks.