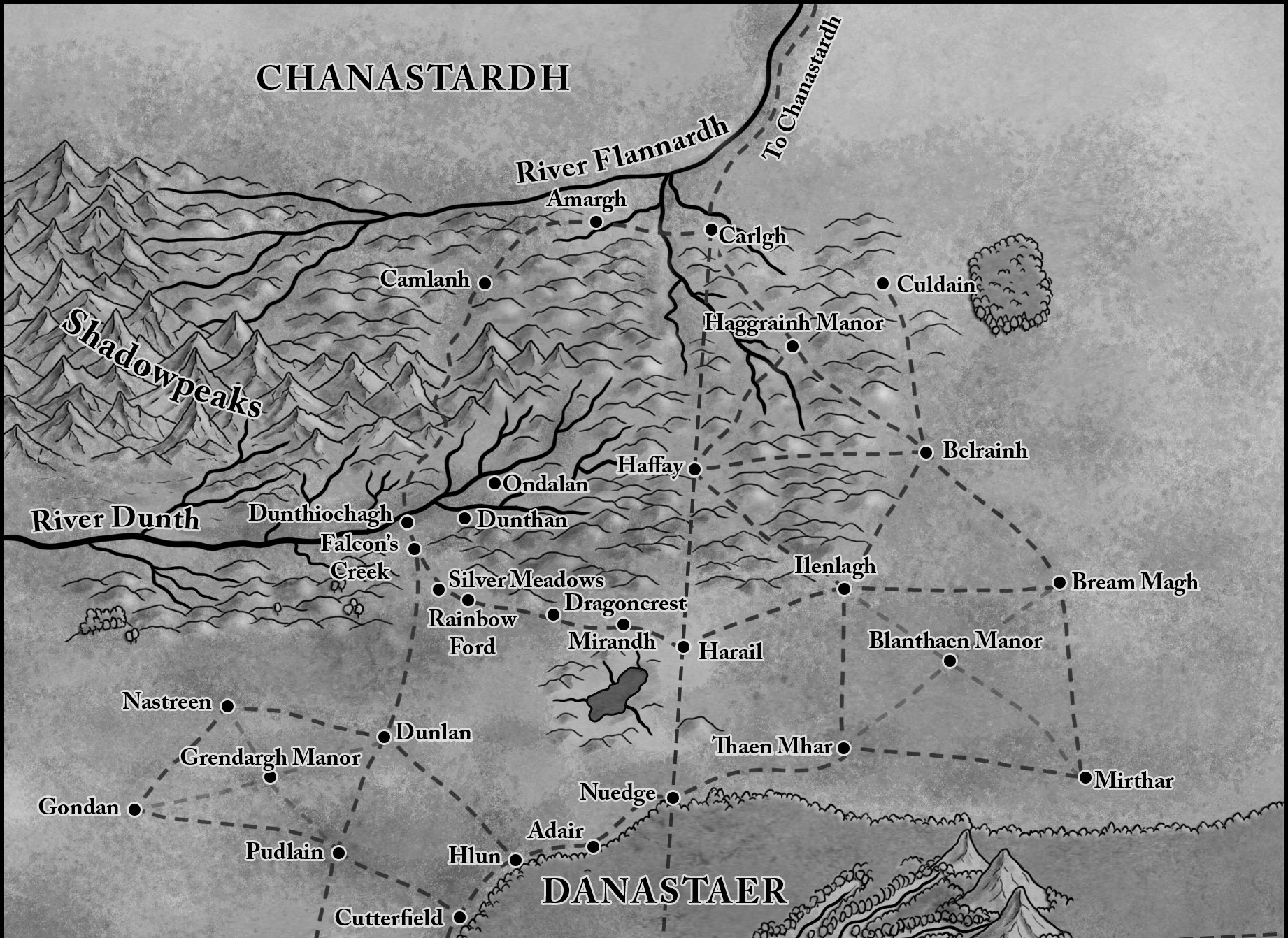

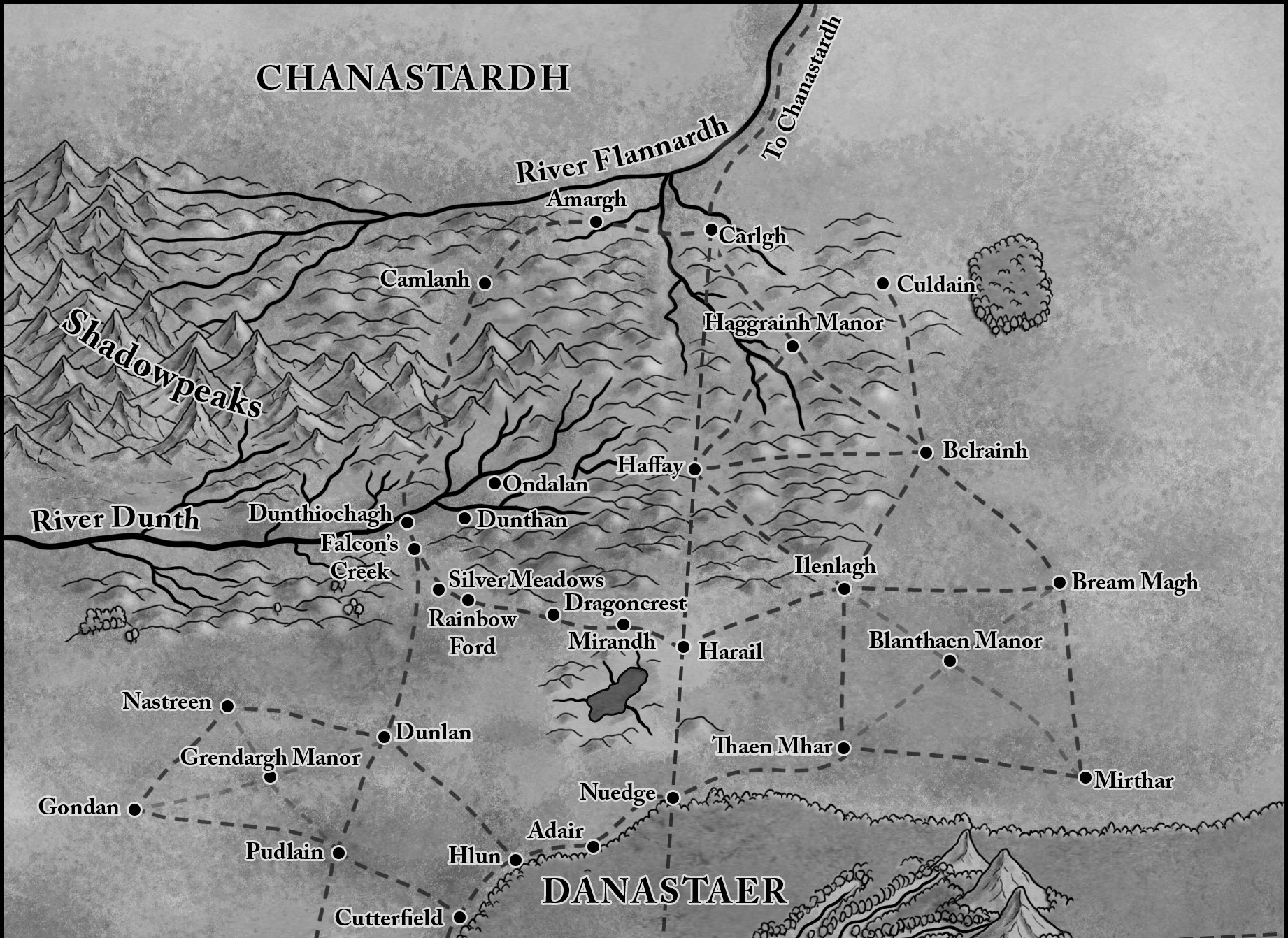

The Human Realms of Taogh: Chanastardh

For tens of thousands of years, Gathran dominated all of Taogh. From the frozen north to the Coast of Steam in the south, from the Bridge in the East to the Broken Coast in the West, Gathran’s culture was ubiquitous.

Yet, some tribes resisted even after they had been subdued by the Gathrani. Exemplary of these were the Chanassi, Targhanti, and Yrenni. These three tribes occupied the lands north of both the Shadowpeaks and the far side of the River Flannardh which served, for the longest time, as a natural border between the northern tribes and Gathran.

Eventually, however, under what can only be described as a false banner operation, the Yrenni “attacked” Gathrani settlers across the river. Gathran sent a Leghan to deal with the problem, and when one Leghan could not do the job, they sent another three.

The Yrenni chieftain protested, sent numerous embassies to Honas Graigh, but King Qandarrheasta was being shielded from their presence. Even when several Lawspeakers and one Upholder tried to intercede on the Yrenni’s behalf, they were summarily ignored. They logged their protests, made sure the true story was written into the Librarians’ Chronicles, and protested again. It didn’t matter. And the Yrenni never forgot.

Chanassi and Targhanti were allied with the Yrenni, and they came to that tribe’s aid when the first Leghan struck. They entrenched themselves in anticipation of reinforcements. For centuries they had observed how the Leghans operated – some had even served as mercenaries in Gathran’s auxiliary forces. They knew what to expect, but none of them were truly prepared for the scale of destruction rained upon them when three Leghans joined the remnants of the first invasion force.

Unlike far too many others, Chanassi, Targhanti, and Yrenni did not sue for peace until most of their settlements had been obliterated and what remained of the seafaring Targhanti had fled east across the sea to the island of T’laen, which they had colonized earlier.

Chanassi and Yrenni were subjugated and had to pay Gathran an impossibly high ransom as reparation. Word of the false banner operation spread all through the empire, and many provinces voiced their support of the three tribes. Some nobles went so far as to sell weapons to Yrenni and Chanassi as rumors of rebellion spread. It’s said that Lliania’s clergy almost declared King Qandarrheasta in Honas Graigh to be godless, something they wouldn’t have dared had they not had the backing of some of the gods. Over time some of the other churches began to side with the Lawspeakers, Upholders, and even Justiciars.

An investigation, with intense questioning of each individual revealed that King Qandarrheasta had fallen victim to a plot led by, of all people, his Justiciar, a man named Jahradd, who had promised his family lucrative business opportunities in Yrenni territory. It had spun out of control from there. Unfortunately uncovering this plot came too late as Chanassi and Yrenni struck against the stationed Leghans, managing to kill First Leghany Kynthirreasta, Qandarrheasta’s daughter.

What followed was a war of extermination that only ended when Chanassi, Yrenni, and Jahradd’s entire bloodline were no more. The king then declared all lands beyond the River Flannardh wrecked, and forbade anyone to cross into the lands of the Chanassi, Targhanti, and Yrenni on threat of death. (The Targhanti might have returned to their old settlements at some point in time, and since Gathran only patrolled the first few miles beyond the Flannardh this was never noticed. ~K)

Gathran’s laws were eternal, or as close to eternal as may be. Even today, most of Breiamhbéo’s laws can be traced back to what the ancient kings of Gathran had chiseled into steeloak tablets to be distributed to every settlement within the empire. The prohibited territory remained until the gods seeded the hemisphere with humans. While the former provinces and territories struggled to overcome being cut off from the ubiquitous bureaucracy and law enforcement and reclaim some of their heritage lost in the deluge of empire, they now faced a new predicament: humans.

That was in the year 500 of the Kalduuhnean Calendar.

The Seeding

We don’t know what the first centuries of Elvenkind were like. No records exist. But many philosophers have theorized that it wasn’t much different from what humanity went through in their own beginning, after the seeding.

Though there is no one left who can tell us what humans were like when the gods first seeded them into the world, we do have scrolls and oral histories to tell us about them. We know that Taogh pounced on the newcomers, though not collectively. The former provinces welcomed the influx of trainable newcomers as history repeated itself, to a degree. Slave-pens, forced breeding, backbreaking labors for a bowl of stew and a slice of bread at the end of the day rose to the fore as quickly as they must have when sunarghs ruled the continent.

Comhara, Claddanh, and Dhachainnh – each continent dealt with the newcomers in a different way, as has been mentioned elsewhere. On Taogh, Gathran’s former provinces saw an opportunity, and without thinking, they took it.

Gathran, however, was the one nation that did not participate. Most likely the Council of Mages, and by extension all the noble families, was too absorbed in the intrigues that had brought low the Empire. A few enterprising individuals decided to domesticate the newcomers, creating their own fiefdoms north of the Woods of Gathran in what would become Dargh and Janagast. They may well have profited from this endeavor, but they also enabled the humans of the area to progress faster than those who had been captured by the other countries and tribes. (It’s curious when one thinks about it. Through selfishness and greed, these entrepreneurs actually gave those two groups a developmental advantage. Even if it was only a headstart of maybe twenty-five years. ~M)

A few other financially inclined families even traveled beyond the River Flannardh to do the same with the humans seeded there. Their enterprise met a rather unfortunate end.

The humans in what is now Chanastardh had half a century to organize themselves, form tribes, villages, even rudimentary weaponry. We can only assume that the gods took a direct interest in them and gave them access to language, crafting, farming, and war. Maybe they saw that area as a new challenge, something pristine, untouched by sunargh or elf. Like all elves, these entrepreneurs thought in elven terms, and while a long-term plan might have looked good on parchment, half a century between conceiving a plan and executing it, allowed the short-lived humans beyond the Flannardh to multiply and organize.

Introduction to the Gods

When missionaries crossed into human tribal lands, they were welcomed as guests. And when they broke Guest Law, as Gathrani were wont to do because of their arrogance, they were butchered to the last elf. A retaliatory expedition organized by a few families, without the support of the army, met a similar fate.

No one taught these humans greed; they learned it all by themselves. Somehow some of them convinced the Stone Lords to craft them some weapons, only to sell them. That’s the only reason why the dwarves created the Places of Contemplation. Since that time, around 550 K.C., the Stone Lords demanded utmost dedication from any petitioner to craft them weapons, not just on Taogh but every other continent. (I’ve heard of elves selling heirlooms as well, it’s not just humans. ~D)

Some gods did not involve themselves that much with human development on Taogh. Then again, they didn’t involve themselves with elven development either. These humans on the far side of the River Flannardh, even now, maintain more shrines to the gods, and venerate more of them, than their brethren this side of the river, but that doesn’t necessarily mean the typical villein knows more about the gods.

Villein, an interesting word. Until humanity’s arrival, elves knew only free people and prisoners or hostages. Sure, there was nobility, usually a term not for disposition but landownership, and one needed a certain amount of wealth and land to be called noble.

The humans beyond the river went further.

At first, life north of the Flannardh was more communal, but eventually the stronger gathered more land and more people around them. As their strength grew, so grew the less fortunate’s acceptance of inferiority. Inferiority became dependence, and soon those who lived in villages and tilled the fields for a pittance were considered property of the nobles. Initial communal inclinations were destroyed by greed on one side and complacency on the other. From the outside, this development seemed to mirror what must have happened in the early days after the Uprising.

“Nobles” began competing with their neighbors. First were the raids then the land grabs, until one fiefdom went to war with another. Canthans (the unit of measurement) were conquered, and villeins found themselves paying homage to a different lord; that is, until the attack was retaliated, sometimes with allies, sometimes to merely accentuate their own decline. The back-and-forth continued for many years.

Followers expected money and land and would even betray their lords if either was denied. Villeins were promised protection, but when that protection didn’t come, they lacked the means to demand their due.

Lawspeakers, Caretakers, Sunpriests, Librarians, all the priests we are so familiar with also played a role in these first human realms, but such progress only came slowly. With no-one to guide them, these petty lords and their followers carved out a life for themselves, far removed from the will of the gods. At least at first.

When exactly Lesganagh and his family made themselves known is difficult to pinpoint. What we can ascertain is that around the year 650 K.C., the humans from across the Flannardh built the first shrines to the gods. It may have been consistently bad harvests or an even more direct intervention, a show of power so to speak. It might also have been contact with Dargh and Janagast, or Madain and Dhomac, or any of the other middling former provinces adjacent to this conglomeration of fiefdoms. Since Librarians or Lorekeepers from those areas don’t keep track of what happens outside their sphere of perception, and the people of what would eventually become Chanastardh had neither Librarians nor Lorekeepers, who knows?

By the time the gods began to make their presence known, bad habits had already taken root. Amongst elves, and those humans directly influenced by elves, genders are equal. In some parts of Chanastardh, however, this still is not the case. Much like petty lords thought themselves above others by virtue of force, they also fostered a disdain for those weaker than them. To them, some people are inferior, and it’s fine to abuse them. Children, women, anyone who couldn’t or wouldn’t fight back was considered weaker. And though many of these lords have changed their ways over the past few centuries, some have not. Most notably the Argram family. Why the gods haven’t directly interfered is up for speculation. Maybe they want to see if society will force adjustment upon the Argrams of Mylaenfor.

With so many traditions already having taken hold in these fledging societies, priestly influence is, at times, odd. Laws had been put in place by lords, and they obviously were slanted towards landowners. Lliania’s church probably had the most trouble. Sure, Lawspeakers and their higher-ups were bound by the laws of the lands they served in, but these laws were rarely written with Lliania’s Scales in mind. The lords of future Chanastardh did not know about those, did not know about their souls being weighed after they died. My guess is that a great many human lords and their underlings, and even the villeins, ended up as chamber pots or scat-cloths upon entering the Bailey Majestic. (It’s difficult to consider those who suffer when one hasn’t suffered. I’m not excusing their behavior, merely pointing out the flaws of a slanted education. And Chanastardh’s education is slanted. ~P)

With laws favoring lords, Lawspeakers and Upholders had to make do with the hand they were dealt. There were no Justiciars in those early days of individual fiefdoms, for the priests of that rank had to be invited by a lord. If that doesn’t happen, they don’t come.

Local laws are always a problem. But when a powerful lord’s relative broke a law and a Lawspeaker couldn’t enforce the laws properly because they were dependent on the lord’s goodwill, things tended to become problematic for the populace. And since a lord or lady viewed themselves as the final authority of any law, they could also change laws on a whim. Compared to even Gathran’s former provinces, these human lands were truly lawless.

Yes, there had been corruption in Honas Graigh or Ma’tallon, but their laws governed everyone. One can only imagine what elven society had been like before tribes had formed.

Gathran probably would have had the strength to teach these humans a lesson, but they were too preoccupied with their intrigues and games. (Actually, Gathran only lacked the will, as evinced by them foiling Breiamhbéo’s attempt to claim the former provinces to the west in around 1200 K.C. ~M)

Change came slowly, usually from outside, when a lord did something to a foreigner, and that foreigner had the wherewithal to retaliate. This was one of the ways Gathran’s Leghans kept busy. Policing actions were seen as a good way to make some money, or obtain a few boatloads of grain. (By that time Gathran had become dependent upon grain from outside their measly empire as the Mages had decreed commoners were to produce only luxury goods for export, turning swathes of farmland into orchards and vineyards.) (Stupid begets stupid. ~D) Whenever a wealthy foreigner was assaulted in Chanastardhian territory, a part of Gathran’s army was hired as retaliatory force.

The Evolution of Chanastardh

In the end, these affronts had become so egregious that several Leghans simply stampeded through what is now Chanastardh. The humans had nothing to withstand these armies, and the lordlings were made to adapt. Some noble houses, notably Argram of Mylaenfor, managed to keep their horrid traditions intact by ensuring that the only people to be victimized were locals, even going so far as to declare other fief’s freeborn untouchable.

Eventually, in a strange reflection of what Gathran had done at the beginning, Lord Durngath of Herascor in the barony of Haeranna began to broaden his domain’s influence. After subduing a number of smaller baronies adjacent to Haeranna, Durngath declared himself king, and named his new realm Chanastardh. How he came to this name specifically, and if it was his intention to incorporate two of the three obliterated tribes’ names into the name, is unknown. (Oh, he most certainly knew. Durngath was the first lord to receive a proper education in the Library of Herascor. A little shithole back then but their Chief Librarian was very well-read, and had received her education in Ma’tallon. ~D)

Durngath’s successors expanded the fledging kingdom, until it encompassed an area much larger than what remained of Gathran. What follows is the Line of Chanastardhian Kings and Queens up until 1475 K.C.

- Durngath, 812 – 825

- Dalmonh, 825 – 830

- Adris, 830 – 860

- Dyfin, 860 – 860

- Dhanhir, 860 – 870

- Cynnog, 870 – 886

- Rhain, 887 – 901

- Tegvan, 901 – 910

- Carwynh, 910 – 920

- Branmor, 910 – 920

- Bran, 921 – 953

- Brattach, 953 – 987

- Cadwyr, 987 – 990

- Ithal, 990 – 1030

- Lleufyr, 1030 – 1053

- Elffodd, 1054 – 1072

- Rhanfriw, 1072 – 1099

- Duach, 1099 – 1113

- Amren, 1113 – 1129

- Rhun, 1129 – 1160

- Mýwr, 1160 – 1174

- Gwylanh, 1174 – 1204

- Queen Tangwen, 1204 – 1238

- Ghiram, 1240 – 1243

- Bledyn, 1243 – 1244

- Ghiram, 1244 – 1272

- Padraigh, 1272 – 1289

- Dubhan, 1289 – 1301

- Myrrin, 1301 – 1306

- Queen Blodwen, 1306 – 1342

- Duach, 1342 – 1380

- Dochàdh, 1380 – 1399

- Duarcành, 1399 – 1422

- Conall, 1422 – 1468

- Drammoch, 1468 – current

While this list is comprehensive, it doesn’t reflect the different dynasties that held the crown over the centuries. Human ambition, like elven, is barely contained at the best of times, and when successions become dubious, as we have seen throughout our own history, things become messy. Since human lives are so much shorter than that of elves, they cram far more ambition into far fewer years. (I’d have said “cram far more stupid into far fewer years” but that’s just nitpicky old me. ~D)

If you enjoy my content, why not buy me a coffee? Click here shoot me a few bucks.

All images, Copyright © 2024, Giulia Conforto.